In today's tough global business environment, strategic negotiation skills are vital for increasing business and profits. Indeed, strategic negotiation skills form part of a group of core competencies required by managers, sales people, and all other business professionals. Managing and negotiating relationships for all stakeholders becomes increasingly: important as individuals and companies conduct business in a global setting.

A critical focus for this article is to assist those people who have to negotiate in an international context. This knowledge is designed to challenge you to consider the three elements presented and to allow you to examine your preparation. The research findings on negotiation styles demonstrates a breakthrough in the styles that we use and also helps you understand why other people behave the way that they do during negotiations.

Everybody within an organization needs to demonstrate a capacity to negotiate effectively; it is no longer the domain of a chosen few. So whether you are involved in marketing, managing in general or an internal support role, you must ensure every interaction with clients, suppliers—and all channels for that matter—is negotiated to a higher level of performance.

A key part of my book, The Creative Negotiator, as well as a recent research project with Dr. Siggi Gudergan, examine the :impact for everyone on negotiating channel relationships and other types of marketing partnerships. This is of particular relevance when companies operate in markets where such relationships are formed frequently, and change occurs in the markets in which they are operating. There is a significant and ever increasing reliance on partnering to assist in the achievement of marketing objectives...

Despite the importance of marketing partnerships, it is disconcerting that an all too large majority of partnerships fail. Businesses a: im to overcome related issues through purposefully negotiated agreements to support the coordination of resources available to the partners.

In the past months, there have been many fine articles in this magazine which have shared wisdom in regards to negotiation and culture. As a foundation of my discussions embedded into this article is, of course, a deep understanding of the culture context of your negotiation.

A successful negotiation, whether that is in the USA Australia or anywhere around the world, revolves around three critical elements:

Types of negotiations

Different possible outcomes

Negotiating Styles

Because these elements are so critical, I've decided to split this article into a background on negotiation and then an examination of each element.

Background

Negotiation has been defined quite differently by a number of authors, researchers and academics. Below are a sample of those definitions:

"The processes by which two or more interdependent parties that do not have identical preferences across decision alternatives make joint decisions" (Bazerman & Carroll, 1987).

"It seems best to define 'negotiation' as including all cases in which two or more parties are communicating, each for the purpose of influencing the other's decision." (Fisher, Emeritus Professor, 1991).

"Communication is at the heart of the negotiating process and is the central instrumental process." (Lewicki & utterer, 1985).

"Negotiation includes cooperation and competition. Common and conflicting interests, is nothing new. In fact, it is typically understood that these elements are both present and can be disentangled." (Lax & Sebenius, 1986).

These def1nitions touch on each of the these elements, and my experience is if you wish to become globally effective or just better in your domestic market, you better be a good negotiator and know how to apply each element.

1. Types of Negotiation

Understanding the importance of identifying the type of negotiation you are involved in often means the difference between success and a poor outcome.

Out of habit, most people enter into every negotiation in the same way. This is not only time-consuming but counter-productive. After all, you don't treat each of your friends and acquaintances exactly the same way, do you? Isn't there someone you know who's a bit more sensitive than most so you have to be extra careful not to hurt their feelings. Or what about those members of the family with such a thick hide that you need to be uncommonly blunt to get the message across?

Everyone is different. Every situation is different. So you should vary your approach to negotiating according to the person with whom you're dealing, and according to what you want out of the deal.

There are three types of negotiation you can choose from which will make the process more productive and successful.

Viewed in a one dimensional linear flow, at one end is the Quick Type, the other end the Deliberate Type, and right in the middle is Compromise Type, which is used too quickly, too often by too many negotiators.

The Quick Type

Use this approach when you need to negotiate in a hurry. The main consideration: you will not (or not within the foreseeable future) be doing business again with that individual or organization.

A characteristic of the quick style is that it's fairly competitive between the buyer and the seller. Both take a position; neither is keen to move from that position. Most academic researchers refer to this type of approach as a 'distributive negotiation'.

The behavioral characteristics exhibited by parties using a quick approach style of negotiation have been researched at length. The person using this type of negotiation sees competition as a necessary part of winning and will focus on the deal at the expense of any relationship.

Lax and Sebenius (1986) describe distributive negotiation as competitive, with both pa1ties attempting to claim benefits for themselves (Roy H. Andes, art. 27, P 125). Thus negotiation type is competitive, for claiming value necessarily deprives the other party of the same value.

This type of negotiation often destroys relationships and the immediate value is seen as the prize.

The Compromise Type

This type of approach to negotiation is often seen as an effective form of negotiation, as each side walks away from the table with some form of deal. The relationship is preserved and an outcome is achieved, often fairly quickly.

This style is used when it is obvious that both you and the other side want to reach an agreement, however there are a couple of points that still need to be resolved. Normally you will hear someone say, "Let's split the difference!"

As I have seen in my work with companies and individuals around the world, this approach often results in a sub-optimal outcome. Nevertheless, as pressure is applied to budgets, forecasts and incentives, this type of negotiation is becoming very popular.

The Deliberate Type

You've probably guessed that if the quick type of negotiation is for use when there's no ongoing business commitment, then the deliberate approach comes into its own when you want to develop or maintain a long-term relationship: when you realize the importance of a deal that satisfies both parties.

The key to the deliberate type of negotiation is knowing that the business will be ongoing—for months, years or even decades. What does this mean in regard to your approach to negotiating? It means you accept that:

The deliberate type requires co-operation and relationship building in an effort to reach an agreement;

It does not develop without a lot of time and hard work;

It means moving forwards, sideways, backwards and back again!

An experience of mine some years ago illustrates the deliberate style in action. I was negotiating an agreement with a large bank in Australia for the supply of computer hardware and consumables for all of Australia and part of the Pacific. After many meetings, the bank's purchasing manager issued a contract for the agreement. As we were about to sign the agreement he paused.

"Just one thing, Stephen," he said. "Our service department uses a lot of consumables. They're not too happy about the discount price." He waited for my response.

Pushing aside the instinctive feeling of frustration that welled up, I carefully studied the whole situation again. I could see that by altering just one delivery we could make up the difference.

With a bit of creativity we solved the problem: he got his higher discount for the department; I secured a lucrative contract. A contract that exceeded my expectations for supplies by 40% in the first year alone.

Were we both happy? You bet.

I have seen many deliberate negotiations turn into a quick negotiation and then back again in a number of hours. This process continues until agreement is finally reached. Just because you decide to adopt a deliberate style does not mean the other side will see it the same way.

The decision about which style to use is in direct proportion to the desired outcome of the negotiation. If you go charging into a negotiation with the approach 'I know what I want and I'm going to get it at all costs' then you can expect an outcome that reflects such lack of planning and consideration.

2. Outcomes

Outcomes vary with each type of negotiation—and preparation is the key. The question of the desired outcomes is ultimately as serious as your choice of negotiating style.

Without realizing that the different outcomes exist, it's difficult to know:

Where to start a negotiation, and

If you've achieved the best outcome.

You also need to know when to turn on your heel and walk out of the discussions. Sometimes the outcome is simply not going to be worth the effort involved to close the deal. It's helpful to have a model against which to measure the desired outcome.

Negotiators who have a number of predetermined possibilities as outcomes have a better chance of getting what they want than negotiators who aim only for the right result.

Aim high, yes—but spend time in preparing more than one desired outcome.

Realistic

This is the best result - both parties are satisfied by the transaction. You may see this result from either the quick, compromise or the deliberate approach. Here we have the classic satisfaction of mutual benefits: both sides feel they'd like to do business again. This is the outcome for which you should strive in every situation.

Although it can and does happen that both sides have that success feeling after a quick negotiation, you would usually win that this kind of outcome is the result of the deliberate approach, where both sides are working together in a creative manner to achieve a realistic result.

Remember the bank purchasing manager who asked me for a better price? In this case, the bank's negotiator used the classic negotiating tactic of adding a 'nibble' to the end of the discussions. It was only by adopting a creative problem-solving approach that the contract was saved. By looking at the delivery and changing the minimum order requirement, I was able to secure the contract.

The result? A personal and professional achievement on both sides. We both felt that the agreement was satisfactory, and a there was realistic outcome to our negotiations.

Acceptable

As we move down the scale, the outcomes start to represent more closely the quick approach of negotiating. In the case of the acceptable outcome, you will get to the end of the negotiation and feel that, while the deal might be acceptable, you could have had a better outcome.

Don't waste time on such thoughts; they're entirely counterproductive.

Here's a little experiment for you to try. The next time you go to buy a product, go to four similar establishments and check the prices. You'll probably be startled to note major differences. In most cases someone has sat down and, with a series of pen strokes, created a price. Again in most cases, people accept these pen strokes as a legitimate price that cannot be challenged!

It can. Ask for a better price. You will be pleasantly surprised.

Always ask for a better deal. Businesses are always keen to move a product or a services better than nothing.

It's an acceptable outcome.

Worst possible outcome

You can be faced with the worst possible outcome in all negotiation types, but it is far more common when you're using the quick type. For instance, if you're trying to negotiate a better price in a retail store and receive a resounding 'NO', it's probably because you're trying to negotiate with someone who doesn't have the authority to vary the terms.

The result? A lose/lose situation. You lose because you don't get the product or service; they lose because they didn't get your business. This is the worst possible outcome for both parties.

If you have been using the deliberate style of negotiation and get the worst possible outcome, it's usually because someone becomes emotionally involved in the process. Is there any need to spell out how dangerous this can be?

I have seen companies lose thousands of dollars due to managerial ego standing in the way of a good deal. I bet you've seen it yourself: reason tends to fly out the window when someone's ego is on the line.

Creative problem solving doesn't have a chance—because someone is standing there stubbornly with only one thought paramount:

"I'm absolutely right and you're definitely ·wrong."

Much as you prefer not to think about it, this could happen to you. You can indulge in a bit of mental sleight-of-hand here to improve your chances; however, if the worst possible outcome is considered as an option, then it is far easier to make a decision and look for creative solutions.

Many negotiators invite the worst possible outcome because of their method of planning—or more accurately their lack of planning. Would you believe that an astounding percentage of negotiators do their planning on the way to the negotiation? Then, when their gamble fails and the worst possible outcome seems about to eventuate, they press the panic button and the deal ends in disaster.

The worst possible outcome is vital in your planning because if you go past this point, the negotiation should stop. Remember the worst possible outcome is still one you should be able to live with.

Think carefully, think creatively, and think ahead.

3. Styles used by Negotiators

Negotiation requires interaction and communication between parties. However, there can be a dramatic difference between how much, and how effectively, parties communicate and interact. Communication between parties can be highly problematic; negotiations can be less combatant with the parties enjoying a mutually beneficial 'win-win' relationship, based on achieving joint goals.

Every situation is different. Therefore, you need to vary your style of negotiation according to the person with whom you're dealing, and according to what you want out of the deal.

This leads to a range of relevant research issues around negotiation behavior such as the use of particular negotiation styles in such relationships.

To deal with this focus, I commenced work with Dr. Siggi Gudergan from the University of Technology, Sydney Australia to examine the existing literature on style and to look at current approaches to negotiating styles.

Negotiating styles are different and the context of the situation will determine which style is most suitable. My experience is that we often become too comfortable with one style and say, 'that's just who I am'.

Existing literature

The literature on negotiation styles provides several conceptual frameworks of negotiation behavior. For example, Thomas and Kilmann (1987) assume negotiation styles are independent of a particular context, and that individual negotiation behaviors can therefore be assessed across situations. Negotiation styles are also relatively stable, personality-driven clusters of behaviors and reactions that arise in negotiation encounters.

There are patterns in individuals' behavior that reappear in various negotiation situations through the mechanism of predisposition toward particular courses of conduct (Gilkey and Greenhalgh 1986). On the other hand, Hall (1969) assumes negotiation behavior is highly influenced by the situation (i.e., interaction between the negotiating parties), Rahim (1983) by the target (i.e., superior, subordinate, peer), and Putnam and Wilson (1982) by both the situational context and the target.

The literature states numerous negotiation styles and associated measurement instruments—most of them being inconsistent and not integrated. For example, Putnam and Wilson (1982) identify three negotiation styles—control, solution-oriented and no confrontation modes. These three negotiation styles are similar to those identified by authors such Mnookin et al (2000) and Weider-Hatfield (1988). Other authors specify five negotiation styles—integrating, obliging, dominating, avoiding and compromising (Rahim 1983) or collaborating, compromising, competing, accommodating and avoiding (Thomas and Kilmann 1987).

Common among those and the various other typologies are two distinct styles: the integrative and distributive styles. An integrative negotiation style is linked to a problem solving orientation in which trust, affinity, and joint gain are emphasized, whereas the distributive negotiation style is linked to a competitive orientation in which power, control, and individual gain are emphasized.

While there are inconsistencies in respect to how negotiation styles are conceptualized in the various contributions, there are also problems associated with the sustentative focus of measurement: many authors do not distinguish clearly between negotiation predisposition, negotiation strategy and negotiation tactics; with many authors using all three foci interchangeably within a single study.

Research Findings

The purpose of this article is not to go into details about the research or the research methodology. Dr. Gudergan and I are more than happy to share that with you. The sole purpose of this discussion is to share the [findings.

The literature is short of empirical studies that unequivocally focus on negotiation styles. This leads to a range of relevant research issues around negotiation behavior such as the use of particular negotiation styles in such relationships. In this paper, to provide a foundation for understanding the intricacies of negotiation behavior and styles, we will first provide a brief discussion of the literatures addressing relevant aspects of negotiation. Then, we will discuss the development and testing of negotiation style measurement scales. This will include a description of the methodologies used for the empirical testing and a description of the findings.

The implications are far reaching for you and your team as you negotiate in the 21st century 'with more and more people.

Let me first broadly discuss the outcomes in the two dimensions that we examined and then the styles that resulted from that study.

Apart from anything else, the research showed that when business and academia work on a problem together, the results can be extremely beneficial in a global context.

Methodologies and Findings

A survey instrument was developed in which 28 statements were listed randomly and respondents were asked to select those seven items which best reflected their position, providing categorical data for each of the items. For this preliminary evaluation, a convenience sample of MEA students has been used resulting in 118 usable responses.

In order to have a more comprehensive assessment, three different scale evaluation methodologies have been employed that can handle categorical data: Factor analysis, Rasch analysis (1960) and Mokken analysis (1971). The summary results of the analysis are to show that the two key concerns were based on the level of cooperation and assertiveness. Cooperation in how the agreement was reached and assertiveness as to the importance of the decision and the process applied to reach the outcome.

From a research perspective, like many others we greatly benefited from previous work by Blake and Mouton (1964) with their Dual-Concerns model. Their model focused on two concerns, on 'self and 'other' as our model will examine the two dimensions of assertiveness and cooperation.

Your negotiation style will be determined by your performance on the two key dimensions of assertiveness and cooperation. From our research, we have formulated a set of seven measurement items for each of the four styles.

This instrument then allowed us to measure and determine the different predispositions negotiators used and it allowed us to explain their style and the four styles in general.

Negotiating with Style ®

Avoiding style: as a stable trait on how to come to an agreement, which is characterized by values and beliefs reflecting an unassertive and uncooperative orientation? This style is often used when the person does not want to engage in a meaningful negotiation. It is often seen in an environment when a junior person is negotiating with a senior manager;

Accommodating style: a predisposition towards an accommodating negotiation style is defined as a stable trait on how to reach an agreement, which is characterized by values and beliefs reflecting an unassertive and cooperative orientation. This style is used when the negotiator puts a considerable focus onto relationship at the expense of the deal;

Competitive style: a predisposition towards a competitive negotiation style as a stable trait on how to come to an agreement, which is characterized by values and beliefs reflecting an assertive and uncooperative orientation. This style is normally used by the 'winner takes all' approach. Focus is on the deal at the expense of the relationship;

Collaborative style: a predisposition towards a collaborative negotiation style as a stable trait on how to reach an agreement, which is characterized by values and beliefs reflecting an assertive and cooperative orientation. This style is often used by people who adopt a more problem-solving approach to the negotiation. Their style is more around the pie can be expanded as compared to a scarcity approach.

A negotiation can be lost in the process (or lack) of preparation. A critical, in-depth analysis of the background of the negotiation, organizational attitudes and culture, as well as a clear identification of the people involved, what the other side needs and wants and what they can afford, is vital before working out what resources and data you must collate to make an informed decision. Preparing and comprehensively researching before a negotiation often solidifies goals and emotions, enhancing the negotiation process and ensuing success.

Conclusion

In summary, you must be clear on the type of negotiation you are about to commence with the other party. Have you determined the different outcomes, what is that walk away point?

Don't allow your principles to become an issue, stay true and finally know which style you wish to apply and use that as part of your negotiations.

The decision that you take as to which negotiating style is appropriate for the negotiation will ultimately depend on the context of the situation that you are dealing with. Your decision around style will be connected to the substantive issues and your relationship with the person/ s in that negotiation.

Our research and experience reveals that too often we don't put enough work into the way that we prepare to manage our style and that of the other party.

This article is designed to challenge your thinking about the four key principles and to look at the many ways that you can be more effective as you negotiate in a fast paced global setting.

Source: Copyright 2005, Stephen Kozicki

Related: Negotiation Workshop

Free Downloads

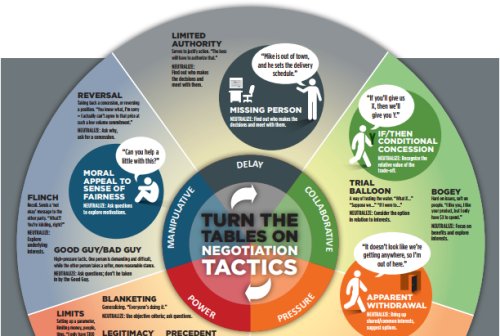

Neutralizing Negotiation Tactics

Public Negotiation Training